From his pew, Junius Whitman could not see the mercy seat, but he knew well enough not to trust it. His vision was blurry, as it always was in those days, and twenty-odd grownups blocked his view. But he had heard the distinct sound of splintering wood when Mr. Stuckey plopped onto the stool moments before—heard it over the cacophony of ecstatic prayer and the shouts of amen and the musical offering of Hilda Rhea Pillwitch, who banged out “I Surrender All” on the piano as though her song were the only thing holding back the very demons of hell. While the adults at Claremore Assembly Church praised Jesus in holy revelry, Little Whit knew the score. The whole spectacle rested on busted legs.

Sure enough, a few seconds later the biomass of prayer lilted to the right, and the stool gave way. The impact of Mr. Stuckey on the chancel sent shockwaves through the new CDX subfloor the men’s group had installed after a leak around the baptismal font last summer. The lectern wobbled dangerously, teetering out over the edge of the first step before falling back into place as though righted by very hand of Jesus. Shouts of “Praise the Lord!” and “Hallelujah!” mingled with orders like “Look here!” and “Watch out!” Some of the elders knelt beside Mr. Stuckey and continued to pray. Two of them picked up the mercy seat and tried to shove the fractured leg back in place. Whit squinted to gauge their success, but a heavy hand landed on his shoulder like the judgment of God.

“It’s time, boy,” Bro. Reinbeck intoned.

He hooked one of his fleshy hands beneath the child’s left armpit. Before Whit could protest, his father did the same with his right. The two men hoisted him up out of the pew and half led, half dragged him up front, through the opening between the altar rails, up onto the chancel and toward the mercy seat.

“It won’t hold me!” he cried.

But Brother Reinbeck was taken by the Spirit, and Cole Allen Whitman was on a mission. His eldest child had always been afraid of storms, but this spring those kid fears had swollen into full-blown panic attacks, which threatened to land Whit in therapy and thus embarrass the family name, such as it was. His kindergarten teacher had recommended as much when Cole Allen picked the boy up from school, saying that advances in child psychology could do wonders for a smart but emotionally mixed-up kid like Junius. That same afternoon, he’d gone straight to Bro. Reinbeck to ask what to do.

“Therapy?” Reinbeck said, working his front teeth up and down as though trying to dislodge a raspberry seed between incisors.

Cole Allen spit on the ground. “I know it.”

“That’s just the way of the world,” the older man answered. “They think they can fix everything by asking you how you feel about it. My Lord.”

“You think it’s—” he glanced warily at Whit—“some sort of demon, causing him to fear?”

“I don’t know that we can pin down a cause,” Bro. Reinbeck said. “But I do believe that, whatever the problem, prayer is the solution. And you couldn’t have better timing.”

Whit fought the urge to roll his eyes. He’d known from the start what his father was up to, going to see the pastor just a few hours before CAC’s healing service. He’d wanted to get Whit on the unofficial docket, to make sure he wouldn’t get passed over in favor of cancer patients or alcoholics or old Mrs. Warner, who always needed prayed over for this malady or that. They’d arrived at church early so that they could get a seat in the third pew, close enough to be a visual reminder to Bro. Reinbeck to give this troubled child a turn in the mercy seat, where sinners and sufferers were brought nearer to the throne of God by the elders.

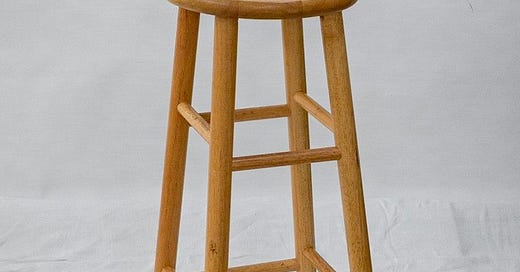

And now his time had come. Six feet from the stool, Whit could finally make a diagnosis of the mercy seat’s injuries. The leg had not been shattered by Mr. Stuckey’s weight, as he’d assumed. Rather, it was cracked lengthwise on one side, right through the hole where the cross support had been. Mr. Stuckey must have somehow gotten a foot onto that poor support piece, judging by the splintered shards that now lay beneath the stool. As long as he could keep his weight pressing down vertically, Whit thought, it might hold. But if any little force pushed him to one side or the other, the stool would collapse. He made a contingency plan to throw his weight to the left if that happened, so as not to land on Mr. Stuckey or the praying elders. When the men spun him around, he could barely make out two parallel tracks in the new carpet, left by the toes of his shoes as his father and the pastor hauled him forward.

He tried one last plea. “I can stand! Just let me stand!”

His cries were to no avail. The men dropped him onto the stool, and for a moment he feared disaster. It held his weight, though, long enough for a few of the elders to crowd in and place their hands on his head and shoulders and back. He could more or less make out who was in front of him, picking them out based on their most obvious characteristics—Mrs. Gleason with her thick glasses, Mr. Koontz and his enormous wristwatch. He could smell old lady perfume and so knew that Mrs. Spietz was somewhere in his neighborhood, and he could hear Brother Reinbeck behind him, binding Satan and casting out Whit’s childish fears and asking the Lord to sweep out the house of his little mind so that it might be a dwelling fit for the Holy Spirit, amen and amen.

Whit didn’t move, though. He’d heard some of his Baptist playmates say blessings over their lunches, and so he knew that for some people amen signaled a conclusion to prayer. Not so with his church. Amen might be the end, surely, but it was more often an all-purpose word—an amplifier, a placeholder, an onramp to the next line of supplication, a question awaiting a response from the brothers and sisters engaged together as warriors in the unseen battle for eternal souls.

Reinbeck went on, praying not only for Whit but for Cole Allen and Bethany Whitman, and for sweet little Libby, not yet six months old. Some of the words had extra syllables spliced into them, and the space between sentences usually contained snippets of prayer language—Humbahlah! Kahkahkah!—that were unintelligible to all but God and so gave Reinbeck’s prayers a special, holy feel.

“Amen, Lord! Amen!” he cried, and Whit could tell this was another gateway amen, the one that would lead into a prayer made entirely out of those nonsense syllables.

It was at this point—and not for the first time—that Whit felt convicted of his unbelief. Earlier in the service, ninety minutes back at least, Bro. Reinbeck had read aloud a story out of the Gospel of Mark to remind them of the connection between faith and healing. A desperate father begged the Lord to heal his son despite his own shortcomings. “I do believe, Lord! Help my unbelief!” the father had cried, a petition which might as well have been the caption for little Whit’s first six years. If there was some belief mechanism necessary for curing his faulty vision or receiving mysterious checks for just the right amount, Whit didn’t have it. He knew Brother Reinbeck’s prayers wouldn’t rid him of his panic attacks because he didn’t—couldn’t—believe that they would. First, he would have to get real faith into his heart, and that would take a confession he wasn’t ready to make, not that anyone was listening at the moment.

“Jesus Lord Christ!” Mrs. Koontz squealed from where she knelt beside fat Mr. Stuckey.

The others continued carrying on with their singing and shouting and praying and tongues, accustomed as they were to outbursts of the Lord’s name in CAC’s healing services. Something in Mrs. Koontz’s voice sounded wrong to Whit, though. He tried to turn his head, but Reinbeck’s hands were placed firmly on each side of his skull as though ready to squish that demon out like the center of a pimple.

“God Almighty!” Mrs. Koontz shrieked. And then, “John Robert!”

The sound of Brother Reinbeck’s given name pulled the emergency brake on the congregation’s ecstasy. Hilda Rhea Pillwitch, who had modulated into “Just as I Am” several minutes earlier, stopped cold in the middle of a chorus. Without the piano, the whole scene devolved into a silence more jarring than anything Whit would experience until his first love affair, still more than a decade off but already set in motion.

Brother Reinbeck released Whit’s head too quickly for the boy to adjust his weight distribution. A half second later, he crumpled to the floor along with the ruined stool. But that was of no consequence to any of the adults. Every eye in the sanctuary was trained on Mrs. Koontz, who was now standing with her back pressed firmly into the corner of the choir loft. She pointed toward Mr. Stuckey with a trembling finger.

“The Lord called him home,” she said. “He’s gone.”

Rogers County Coroner Don Ray Spietz confirmed Mrs. Koontz’ diagnosis, adding that the poor man appeared to have been dead for half an hour before anyone in the congregation realized it. Don Ray enlisted four men to roll the body into the thick black bag for transport and two more after that to lift it onto the long-suffering gurney that would bear Mr. Stuckey along the Glory Land Way. The men rolled him down the center aisle to a chorus of sighs and sobs, tears flowing from the eyes of every church member as thunder from a late evening storm rumbled in the distance. Whit shifted his weight from one foot to the other.

“We should pray,” Bro. Reinbeck said once the doors to the hearse had closed. “Gather up, y’all.”

The forty-odd souls that comprised the faithful remnant dutifully circled up around the altar. Whit joined them, hoping no one picked up on his reluctance. It was one thing for prayer to fail a doubting soul like his. But for faithful Mr. Stuckey to drop dead on the altar, right there in the middle of all the hand-laying and Satan-binding? If such was the Lord’s plan, Whit couldn’t see how it was supposed to help his unbelief.

Pink lightning flashed through the windows. A few seconds later, peals of thunder shook the walls. Whit’s stomach churned.

Thankfully, Bro. Reinbeck tapped Alton Jennings for the closing prayer, and the old man sensed that the moment called for an economy of words. Two minutes later, Whit was climbing into his father’s pickup. He buckled his seatbelt—a habit he’d picked up from a television ad campaign—and waited while his father stood by the tailgate listening to Brother Reinbeck. Cole Allen nodded. Kept nodding while the preacher laid a beatific hand on his shoulder. Lightning flashed through the windshield. Whit counted—one one thousand, two one thousand, three one thousand. At four, a loud crack of thunder caused the men to jump. Whit felt sweat on the back of his neck. The bolt originated less than a mile away, if the counting method he’d learned from his teacher was correct. He rapped his knuckles against the rear windshield of the pickup. Cole Allen grinned and shuffled toward the driver’s side door. As he pulled back on the handle, he told Brother Reinbeck that he got off work at 4:00 tomorrow and to bring him—he didn’t clarify to whom he was referring—by the house about 4:30. Cole Allen started the engine but left the transmission in park. He drummed his fingers on the wheel. His eyes danced with adrenaline.

“Did you feel it?” he asked.

“When Mr. Stuckey hit the floor?”

“No, son! The Spirit.”

“Yeah,” he said. “I felt it. Can we go?”

“Don’t lie to me, now. Did you receive a healing? Or a blessing?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“Don’t lie to me, son.”

“I’m not lying. I just want to go home.”

“Do you feel any different?”

“No.”

For at least the millionth time in his young life, Whit wished to be free of the particular chain with which he was most tightly bound. Although he as yet lacked the words to express it, Little Whit knew in his heart that he was a slave to the truth. No matter what narratives his teachers or parents or anyone else offered—no matter the friction he caused by his quiet yet resolute dissent to those narratives—he could not help but think and speak of the world as it truly was, at least in his understanding of it. Such a trait created all manner of difficulty for Whit, both within his still developing psyche and out among the adults in his life—parents and teachers and church people, mostly. If Whit had a choice in the matter, he would have no doubt determined that bald-faced honesty was not worth the price he paid. But he was wired for no other disposition. And so he soldiered on. Held his tongue while his father considered the situation.

“Maybe you just don’t feel it yet,” his father said. “Could be that your kind of healing takes a while to go into full effect.”

Meanwhile the storm drew nearer. They drove northward out of town toward the farm they rented from Mr. Jennings, trailed by billowing clouds illuminated by flashes of lightning.

Big drops of rain assaulted the windshield. Whit squeezed his eyes shut. Hail would be next, and then the roar of nature’s perfect killer. He could already imagine what people would say to his poor mother when the twister wrapped Cole Allen’s pickup around the tree. It was the Lord’s will. Little Whit has joined the angel choir. At least you and the baby were safe.

His father, on the other hand, might as well have been driving on rays of heavenly sunlight. He cracked his window and lit a cigarette and even hummed to himself. He was happy, Whit realized, which only heaped frustration on top of the boy’s misery. If he had any sense of his only son’s distress—even more so, of the tragedy of Mr. Stuckey’s sudden demise—Cole Allen didn’t show it. He eased the pickup into its place in the driveway as though the world was all honeysuckle and butterflies.

Nickel-sized pellets of hail stung Whit’s skin as he ran from the pickup to the porch. He bounded up the steps, past his mother and into the laundry room. Reached down for the metal ring on the trap door and pulled it open, revealing a short wooden ladder that led to the crawl space. He settled into the hideout he’d constructed out of old pallets and layers of blankets, arranged with the help of his mother and only just tolerated by his father. As he eased the door closed, he could hear Cole Allen bragging that soon, thanks to his prayerful intervention, their son would be able to face the weather like a man.

Here in his hideout, though, little Whit had no interest in facing up to anything. He let the safety of his very own space envelop him, the smell of cinder blocks and crackle of Visqueen as much a comfort as the psalmist’s rod and staff. The block walls around him and sub flooring above muffled the sounds of the thunder and hail and left him to ponder his old plastic toolbox and the assortment of fragile things he’d placed therein. A half-chewed baby blue pencil with “Houston Oilers” printed in pink. A plastic ruler with tiny portraits of all the U. S. presidents, Washington through Clinton. A yellow sperm whale eraser that was smooth to the touch. These were of no account to the world, and so it fell to Whit to protect them. He settled them into the box with his flashlight and snacks, and he promised them they’d be safe here with him, below the tumult, where flying debris couldn’t pierce them and downed trees couldn’t crush them.

On the main level of the house, the world was not so serene. He could hear his parents moving across the floor, pacing from one room to the next the way they did in the early phase of an argument. He traced their footsteps with his flashlight until they settled into their bedroom. He slid over to the edge of the pallets and lifted his ear up to the hole in the floor through which the TV cable ran.

“I never seen anything like it,” Cole Allen was saying.

“You see something like it every time you go to church,” Bethany Whitman replied. The floor beneath her creaked gently as she bounced the baby. “Anytime Johnny Reinbeck gets to praying it’s a goddamn circus.”

“A man died tonight.”

“I know. And I’m sorry, truly I am. I didn’t have nothing against Mr. Stuckey. But you kept our boy, who has enough problems of his own—”

“Which he was healed of tonight.”

“—and you kept him there with a dead man just so you can feel important.”

“It’s not like that. The Spirit—”

“And Whit’s in the fucking crawlspace. He ain’t healed.”

A pause, and then his father’s voice. “Give me the baby.”

“Why?”

“Because I don’t want her first words to be some sort of cussing she learned from you.”

“Jesus Christ.”

“That’d be better—just not the way you say it. Now hand me the baby.”

“No.”

Whit held his breath. The storm should have passed over by now, which should have sent his mother stomping across the floor and yelling for him to come get ready for bed. The fact that she did not told him the tension between his parents might snap into open warfare at any moment. He adjusted his position and listened, growing surer by the second that he knew exactly what lay at the center of the conflict. His father’s next words confirmed his fears.

“It’s our Christian duty to care for the prisoner,” Cole Allen said.

“They can find another Christian then.”

“I’ve got a gift for this sort of thing. It’s an offense to the Lord if I don’t do it.”

“Johnny’s just flattering you. You ain’t nothing.”

“I’m more than you ever been.”

Whit squeezed his eyes shut. Tried to pray away the argument. At least twice in his memory, someone from Brother Reinbeck’s prison ministry had come to live with the Whitmans after finishing up his sentence with nowhere to go. The first one Cole Allen brought home, a balding man about fifty years old who went by “Scooter,” was nice enough. He stayed three months before hopping a Greyhound to California to live with the only one of his wife’s four children that he claimed as his own. Whit couldn’t remember the name of the second man, only that he’d gotten drunk and pinched his mother on the behind, and that she’d clocked him with a frozen dinner so hard that his glass eye fell out onto the table.

“We’ll move the crib into our room,” Cole Allen said. “It’ll just be for a little while.”

“We ain’t got money for a little while, even.”

“Don’t matter. The Bible says what it says, and it says to care for the prisoners. That’s from Jesus.”

“Jesus never paid a damned penny for rent.”

“Maybe it was Paul that said it.”

“God, I’m tired,” Bethany moaned. “We can’t keep doing this, not with another baby around. You call Johnny back and tell him no.”

“I can’t do that.”

“I’m so tired, Cole Allen.”

“That ain’t my fault.”

And that lit the fuse. Even down in the crawlspace, Whit could hear his mother’s breaths getting shallow, her heels tapping on the floor as she fidgeted. If she held onto Libby, things might die down before the worst could happen. But Whit could already hear her footsteps, stomping across the hall and into the kids’ room, where she would stow the baby in the crib while the parents fought.

He lay down on his side and curled his body around his collection of fragile things. Hoped joy would come in the morning.

CLICK HERE to purchase the print copy.

CLICK HERE for the full audiobook.

Funny in the manner of Frank O’Connor’s short stories! Great reading, too. Looking forward to more!